The information presented on this page may be dated. It may refer to situations which have changed or people who are no longer affiliated with the university. It is archived as part of Mississippi State University's history.

A relatively new pathogen has been creeping insidiously through cotton fields across the Southeastern U.S. Two Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station (MAFES) scientists are striving to better understand how it infiltrates cotton plants and how best to defend against this elusive adversary.

The cotton leafroll dwarf virus, or CLRDV, was first observed in 2018 and officially reported in North America in Alabama in 2019. The virus that causes cotton leafroll dwarf disease, which interferes with normal plant development, is now found across the Cotton Belt. CLRDV hasn't led to widespread damage in the U.S. yet, but scientists and growers say the potential exists.

Dr. Nina Aboughanem, co-principal investigator of the study and an associate research professor in the Institute for Genomics, Biocomputing and Biotechnology affiliated with the Department of Agricultural Science and Plant Protection, made the first discovery of the virus in Mississippi in 2019.

"When our colleagues in Alabama observed symptoms such as leaf reddening, crinkling and curling, as well as deformation of cotton bolls, it triggered an alarm around southern cotton-producing states," she said. "Soon after I first discovered the virus in Mississippi, we found that it was already widespread here."

CLDRV is a challenge to diagnose, which is why it went undetected for so long. To the naked eye, symptoms like brittle leaves and apparent nutritional deficiency can have more than one root cause, and symptoms vary among different varieties of cotton plants.

"This is the first time that CLRDV has threatened American cotton, but historically, it has led to as much as 80 percent yield loss in the South American commercial cotton industry," said principal investigator Dr. Sead Sabanadzovic, a professor in the same department.

The MSU study, begun in 2020 and led by the husband-and-wife team, was initially funded by Cotton, Inc. and MAFES. After partnering with Dr. Jodi Scheffler, a scientist at the USDA-ARS Midsouth station in Stoneville, and Dr. Tom Allen, an extension and research professor at MSU's Delta Research Extension Center, the group received $325,000 from USDA's Agricultural Research Service to continue their research.

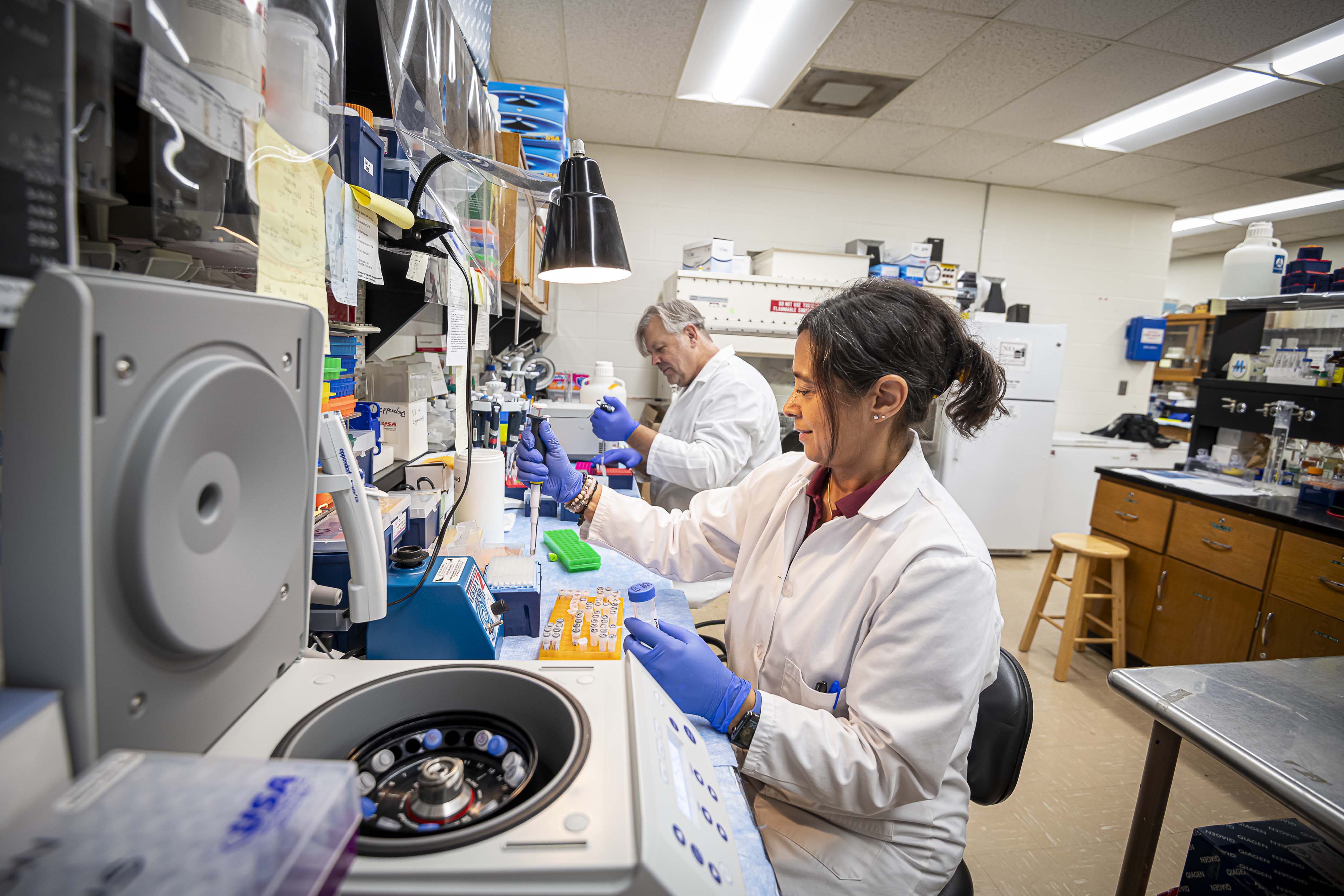

Aboughanem developed an in-lab diagnostic test using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, or RT-PCR, to reliably and more quickly detect the presence of the virus-a critical early step. This technique, which is also frequently used to detect the virus causing COVID-19, checks for small amounts of genetic material from a pathogen, such as DNA and RNA, and can detect disease in its earliest stages.

"A particular improvement of our test compared to others is the amplification of specific nucleic acids from the cotton plant along with those of CLRDV and its simplification by combination of different steps," she said. "This modification produces results within a few hours, increases the reliability of the whole test, and ensures that all phases of a multi-step process are executed properly."

Genetic variability of CLRDV further complicates predictions of the virus's biological impact on its host, as some variants may be more severe than others. Aboughanem's diagnostic tests can detect the entire gamma of genetic variants present in Mississippi's cotton fields and in neighboring states.

The team also discovered secondary hosts-native weeds-that act as reservoirs for the virus over the winter. Aphids that act as vectors are likely to spread the virus from the infected weed or cotton plants once they are planted and to mediate in-field spread from an infected plant to a healthy plant.

The team established that the virus's impact on U.S. cotton is less severe than in South America, likely because of the differences in CLRDV strains, cotton varieties, and environmental conditions. However, since the beginning of the study, the scientists have learned that this virus is even more complex than they had assumed.

"The first year, 60-70 percent of our samples tested positive for the virus, but that number has dropped significantly since then because the symptomatology is tricky," Sabanadzovic said. "Its spread may also vary from year to year because environmental conditions greatly influence the presence of infected weeds and vectors."

The team has learned that CLRDV is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to potential pathological threats to the U.S. cotton industry. They continue to combine "boots on the ground" approach (field surveys) and apply the most advanced and unbiased molecular lab methods, like high-throughput sequencing, to determine other viruses that are present and to understand whether they may cause harm under certain conditions.

As they got deeper into the research, the MSU team discovered another virus that is integrated into the genome of upland cotton-the most widely cultivated species of cotton in the world. The results of this research have been recently published in a reputed peer-reviewed journal.

"Just because a virus's sequences are present in a host plant genome doesn't mean it will cause harm," Sabanadzovic said. "We are currently researching these integrated viral sequences to determine what they represent and whether they may go from 'dormant' to an active, infectious form in the presence of certain external factors."

Unlike fungicides or insecticides, there are no chemical treatments for viruses. Controlling CLRDV, then, relies on preventing infections and good agronomic practices, such as planting virus-free material, planting resistant or tolerant varieties, and controlling insects or other vectors that may spread the virus from plant to plant.

"In virology, we cannot treat the problem by healing already infected plants, so our solution is prevention," Aboughanem said. "That is why it's important to study the biology of the virus and its variants so that we can avoid the kinds of economic havoc that we've seen in the South American cotton industry.

This research is funded by USDA Agriculture Research Service, the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, and Cotton, Inc.

In virology, we cannot treat the problem by healing already infected plants, so our solution is prevention.

Dr. Nina Aboughanem

Behind the Science

Nina Aboughanem

Associate Research Professor

Education: B.S., Agriculture, St Joseph University, Lebanon; M.S., Plant Virology, Mediterranean Agronomic Institute of Bari, Italy; Ph.D., Plant Virology, University of Bari, Italy

Years At MSU: 12

Focus: Diversity, evolution and taxonomy of viruses

Passion At Work: We are truly passionate about discovering and characterizing part of the enormously diverse virosphere, or virus world, and have fun doing it.

Sead Sabanadzovic

Professor

Education: B.S., Agriculture, University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina; M.S., Plant Virology, Mediterranean Agronomic Institute of Bari, Italy; Ph.D., Plant Virology, University of Bari, Italy

Years At MSU: 20

Focus: Diversity, evolution and taxonomy of viruses

Passion At Work: We are truly passionate about discovering and characterizing part of the enormously diverse virosphere, or virus world, and have fun doing it.