Counting the Cost

Redesigning farm policy in an era of digital agriculture

By: Vanessa Beeson

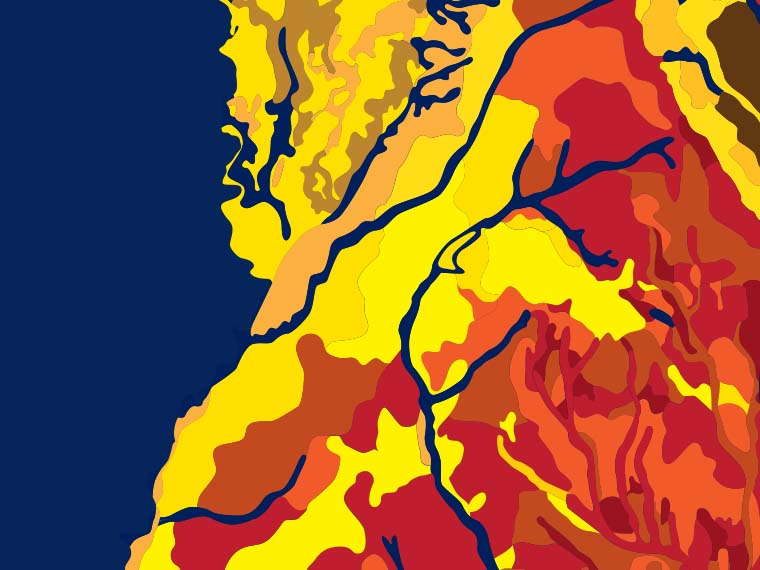

Mississippi's 82 counties contain six major soil ecoregions with over 70 different soils. These ecoregions are the Delta, Loess Hills, Upper Coastal Plain, Blackland Prairie, Lower Coastal Plain, and Flatwoods. This graphical illustration of varying soil types is based on an original map available here. (Illustration by Dominique Belcher)

The information presented on this page may be dated. It may refer to situations which have changed or people who are no longer affiliated with the university. It is archived as part of Mississippi State University's history.

THE FARM BILL has been around for nearly 90 years. During that time, agriculture in America has changed drastically. As farming transformed through advancements in mechanization; seed, herbicide, and insecticide innovations; and, ultimately, the development and implementation of precision agriculture; the massive, multi-year law that governs a variety of agricultural and food programs sought to keep pace. Each new version of the law, administered by the United States Department of Agriculture's Farm Service Agency, tries to adapt to the ever changing landscape, in order to better protect the hardworking farmers that feed, clothe, and fuel the world. To continue the quest for seeking policy improvements in a changing world, researchers in the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station have embraced the ambitious task of redefining farm policy in the era of digital agriculture.

Dr. Keith Coble, professor and head of the Department of Agricultural Economics, hopes the research will help create farm programs that work better for producers.

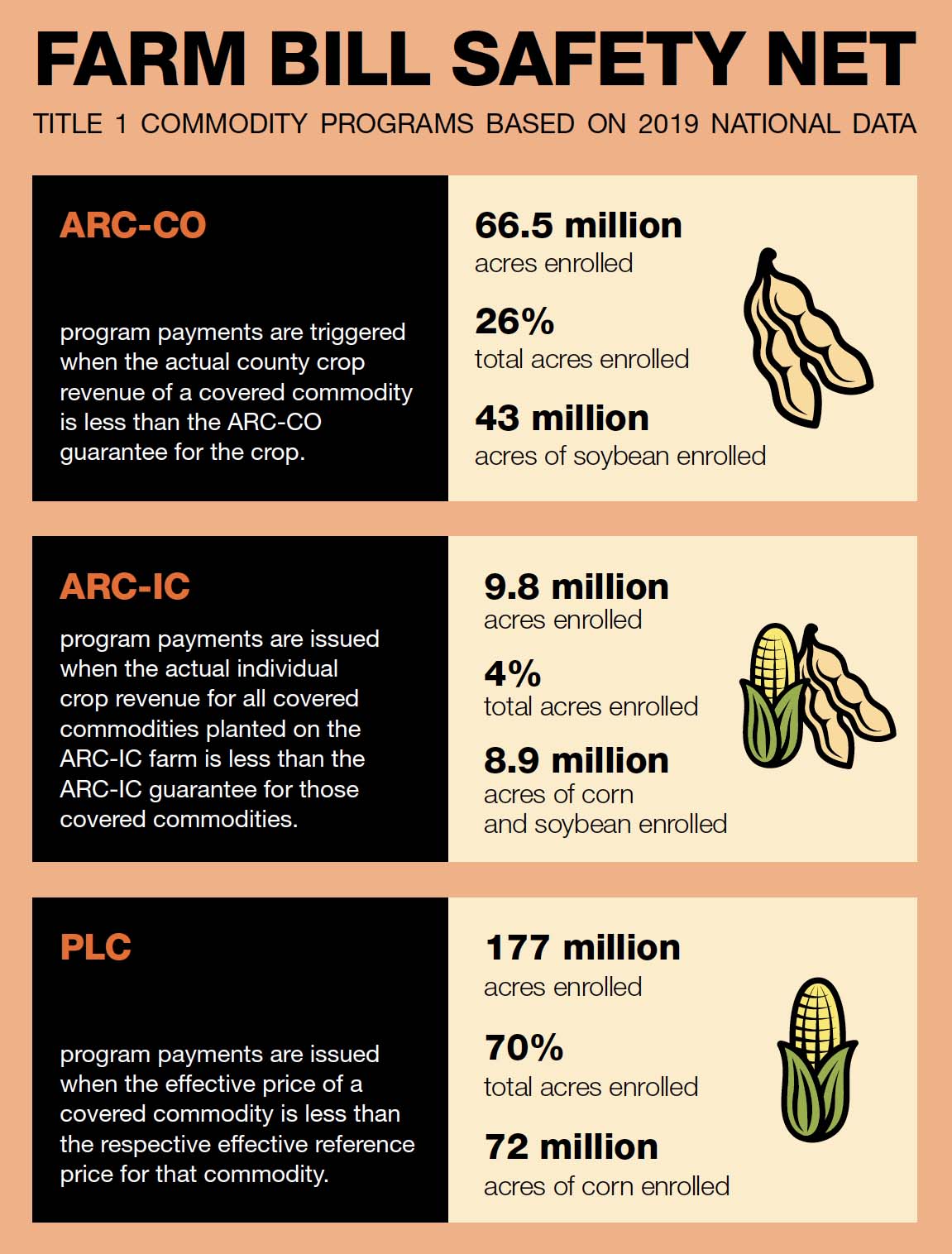

Coble explained that programs enacted by the Farm Bill, such as the Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) commodity program and other traditional crop insurance programs, are county-triggered. Each relies on yearly average county yield data, as reported by the USDA's Risk Management Agency (RMA), the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), and other sources.

"The basic building block of many of these programs is the experience at the county level," Coble said. "Across the U.S., the political boundaries of large and small counties alike were drawn in the 1800s. These jurisdictions are not designed to be homogeneous crop producing areas."

He pointed out that county-triggered programs are sometimes inaccurate in payouts, in some cases compensating farmers who haven't experienced a loss while failing to pay those who have.

"Under these county-triggered programs, there have been times when a farmer experiences a loss that the county data doesn't indicate so they're unhappy because a county-triggered program didn't help mitigate the loss. Conversely, it's costly when the county-triggered program indicates a loss and pays someone who didn't actually experience a loss that year," Coble explained. "This is about making these programs more precise, so they help farmers who need it, when they need it most."

The four-year $400,000 project, funded by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, aims to find a better way to determine premium rates for crop insurance and ARC.

Dr. Ardian Harri, professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics, said that first, the researchers plan to replace county data with homogeneous areas of production in terms of both average yield and yield variability.

The team is using multiple sources of digital data to better estimate yield while integrating high resolution soil and weather satellite imagery, and other precision agricultural data.

"We are creating and identifying homogeneous areas in terms of yield distribution," Harri explained. "A distribution has a mean and a variance. Variance is very important for risk and crop insurance rate determination so we're hoping to determine homogeneous areas of risk, not just by the mean average yield but also by yield variability."

Harri, who is most excited about answering the research questions at hand, pointed to the team's next two objectives.

"We are trying to figure out if soil is an important factor in determining the accuracy of crop insurance rates, as well as hoping to better understand specifically the effect soil has on yield variability. Next, we hope to improve the accuracy of crop insurance rates for both the area crop insurance and ARC by taking advantage of the homogeneous areas developed in this study incorporated with the soil information to build a better model for estimating risk and premiums," he said.

Dr. Xiaofei Li, agricultural economics assistant professor and production economist, is focused on the soil component.

"All of us on the team think that county yield data is too coarse to serve as a metric in terms of determining crop insurance premium rate and risk management because clearly there are all kinds of fields within any given county," Li said.

Li is building maps that detail soil data to redefine soil homogeneous areas. From there, Li said farmers can be aggregated into groups based on similar yields, soil type, and other factors, and assigned a similar premium rate.

"My goal in this project is to estimate the functional relationship between the yield and yield risk with different fields, weather, soil, and other factors in high spatial resolution," Li said. "Our long-term goal is to use this data to better classify the crop yield risk and, ultimately, the premium rate in a more accurate way."

Dr. Eunchun Park, agricultural economics assistant professor, is focused primarily on building the model to better estimate risks and premiums. He said the work will reduce two market situations, which can occur in crop insurance: adverse selection and moral hazard.

Park explains that adverse selection in insurance is the tendency for high-risk individuals to buy into insurance programs while low risk individuals opt out. Moral hazard is based on the idea that those insured individuals will then take bigger risks since they're protected, should a loss occur.

"If the premium is not correctly rated, only risky people tend to participate in the program. We want to minimize both moral hazard and adverse selection. We can do that by designing a sophisticated area-based program," Park said. "Our ultimate goal is to develop a crop insurance rating model based on location information, climate and soil similarity, and more to increase both the farmer's utility and the effectiveness of the programs."

This research is funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station. Master's students on the project include Zach Ishee, Cannon Kent, and Amadeo Panyi.

Across the U.S., the political boundaries of large and small counties alike were drawn in the 1800s. These jurisdictions are not designed to be homogeneous crop producing areas.

Dr. Keith Coble