The information presented on this page may be dated. It may refer to situations which have changed or people who are no longer affiliated with the university. It is archived as part of Mississippi State University's history.

COTTON IS ONE OF MISSISSIPPI'S top agricultural commodities. With 780 farms and 1,600,000 bales produced in 2019, it is clear why Mississippi ranks third in the nation for cotton production. Cotton's role extends well beyond the state line, however, as it is found in clothing, fabrics, and even cosmetics across the globe.

With a role so large, the quality of cotton is vital. Dr. Filip To, MAFES researcher and agricultural and biological engineering professor, is collaborating with the USDA-ARS to detect contaminants in cotton before the final stages in the ginning process.

"We are trying to find the solution that will remove the plastic before it gets to the gin," To said. "We want to address the issue of plastic contaminants in the cotton being ginned, and we want to get a more contaminant-free cotton."

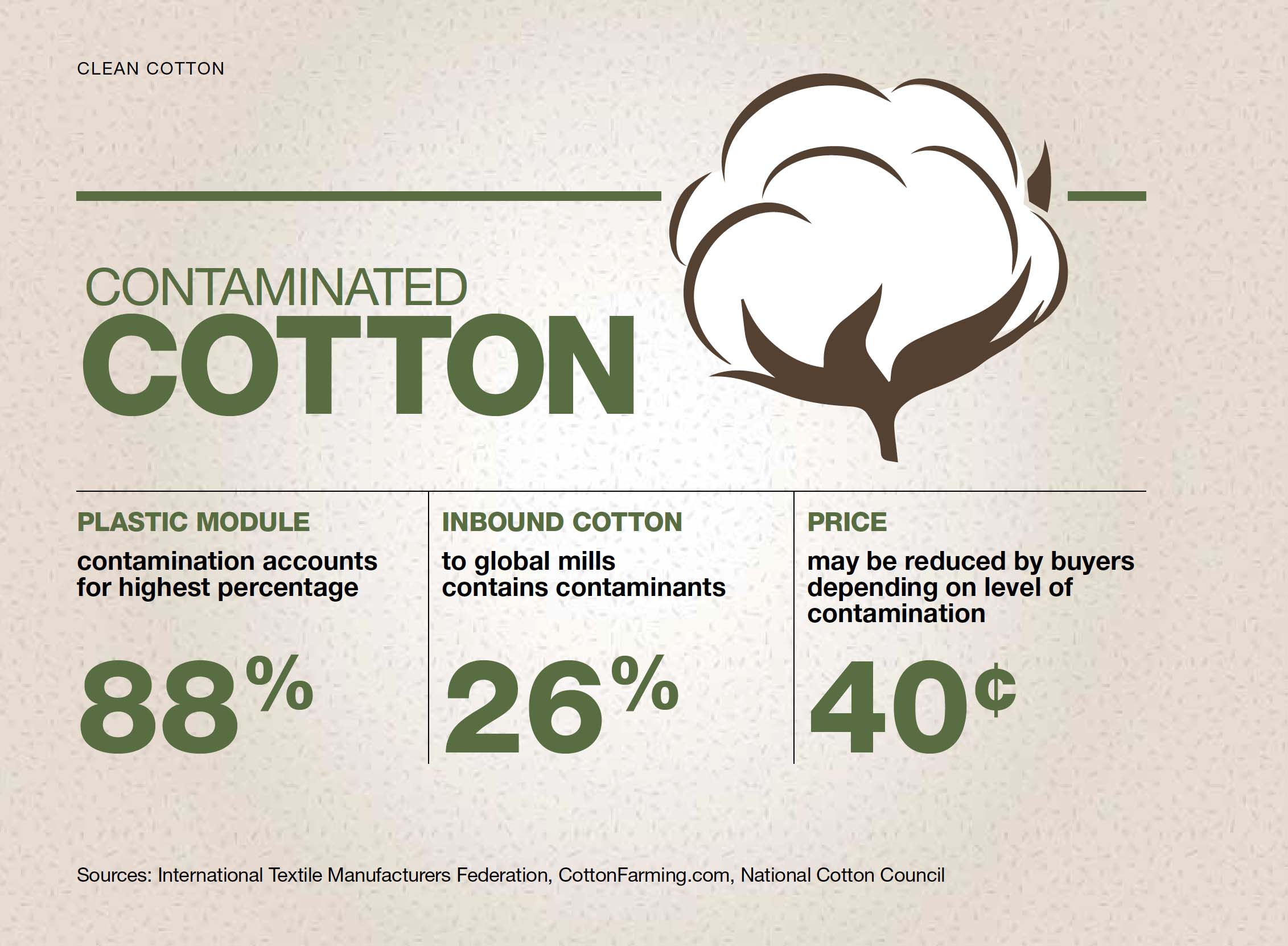

Plastic contamination of cotton is a grueling yet common issue in today's process of cotton ginning. Most often, plastic can be found in cotton from trash that has been blown into the fields and picked up by machinery or even the plastic wrap used to secure bales or modules of cotton. Inside the gin are hundreds of rotary saws that rotate at a high speed to separate the seed from the fiber. When plastic is present, however, it also gets cut into smaller pieces, which become embedded into the fiber. To said the presence of plastic in cotton can significantly decrease the value of the product.

"When a bale of cotton from an area is discovered to have contaminants, they say it comes from that particular region, which can affect the reputation of all cotton from that area," To explained. "As a consequence, the product from that locale becomes less desirable as fewer buyers want it. From the farmer's point of view, they need to be sensitive to make sure their cotton is contaminant-free as their reputation, and the reputation of their neighbors, depend on it."

The team is also examining the issue of moisture content in cotton gins. Moisture content of the cotton correlates with the productivity of the gin and the quality of the cotton. In order to aid in the separation of fibers, seeds, and sticks, the moisture content of seed cotton must be perfect at the level necessary to promote adequate cleaning, yet not so low as to cause permanent damage to the fibers. Imprecise moisture content allows for weakening of the fiber, thus causing it to break, resulting in fiber length reduction. Final bale moisture content outside the range of four to seven percent may lead to production and storage issues further along in the production chain.

The three-year project is being carried out in three phases, beginning at Mississippi State before moving to the USDA-ARS Cotton Ginning Research Unit in Stoneville, Mississippi. The plan is to create a machine vision system that would be used in the gin to detect the plastic in the cotton, remove the contaminant, and discard it.

The second year of research is underway. The current stage observes whether the machine can recognize the plastic contaminants in the cotton. The machine is tested for accurately detecting the contaminant and characterizing its performance. Phase two will look at moving cotton and scale-up issues. The team will take a sample of cotton, feed it through a conveyor, and examine whether the machine detects, removes, and discards the contaminated part. The final phase moves the research and cotton to the gin, putting it all together.

The impetus of the project stems from the volume of plastic contamination that has increased over the years.

"Plastic contaminants have increased over the years, and so far, there is not a good solution to handle it," To said. "This is a global problem and there are currently limited solutions to curb the volume."

The current method for removing plastic contamination relies heavily on presorting the modules of cotton by hand before being fed into the gin. Some automatic detection technology is also used inside the gin including many cameras and high-performance electronics or computers. Both methods are currently unsustainable and they have many issues. To and his team are interested in shifting to a method that uses very little human involvement by automating the detection and separation process.

Farmers are hit heavily by the results of contaminated cotton, but consumers face implications, too. To said consumers see an increase in prices when contaminated cotton is present.

"In clothing, a contaminant degrades the quality of the clothing. When textile industries see bales of cotton with contaminants, they penalize the grower and deduct much of the costs," To said. "This then affects the price of the clothing you buy. Fabric with contaminated cotton is deemed flawed, making the clean material rare and, as a result, more expensive."

Joe Thomas, research leader at the USDA-ARS Cotton Ginning Research Unit in Stoneville, Mississippi, added that contaminated cotton has a very difficult time competing in the market.

"We can all agree that we like the feel of wearing cotton, but it is not the least expensive of fibers," Thomas said. "As a result, it has a tough time competing in the marketplace. When you throw plastic contamination into the mix, it requires additional processing, and it increases yarn and fabric prices. You have a high price fiber that's desirable, but you're adding costs to that fiber, putting it at an even worse competitive position."

Thomas believes eliminating plastic contamination will be beneficial for all involved in the industry.

"Plastic contamination is a major industry concern. If somebody can create a method or process to mitigate the impact of this contamination, or better yet eliminate it all together, it would be a tremendous benefit to the cotton producers, the ginners, the merchants, just about everybody in the value chain," Thomas said.

Plastic contamination has been an industry-wide issue for some time now, and research conducted by the ARS and institutions such as MSU are vital to diminishing the problem.

"Plastic contamination is by far the most challenging issue facing the U.S. cotton industry, at least that we have seen in many years. U.S. cotton no longer enjoys the non-contaminated premiums that it once had," Thomas added. "The implications are huge-loss of market share to countries like Australia and Brazil, price discounts, loss of income to producers, the increased cost of ginning-it's a pretty long list, and it's an industry-wide problem. That's why you see groups like the ARS and universities like MSU collaborating on projects, and the contamination project, in particular, is being addressed by multiple agencies industry-wide."

The newly appointed research leader is excited about potential developments to follow the research, as well as the journey it will take him on.

"The potential for technological breakthrough in either contamination detection or moisture control excites me," Thomas said. "I've been in the industry for over 45 years, but I'm new at being the research leader, so that adds to the excitement. It gives me the opportunity to share my years of experience with younger engineers and scientists coming into our industry."

This research is a non-assistance cooperative agreement between the USDA-ARS and Mississippi State University. This research is funded by the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station.

Plastic contamination is by far the most challenging issue facing the U.S. cotton industry, at least that we have seen in many years. U.S. cotton no longer enjoys the non-contaminated premiums that it once had.

Joe Thomas