The information presented on this page may be dated. It may refer to situations which have changed or people who are no longer affiliated with the university. It is archived as part of Mississippi State University's history.

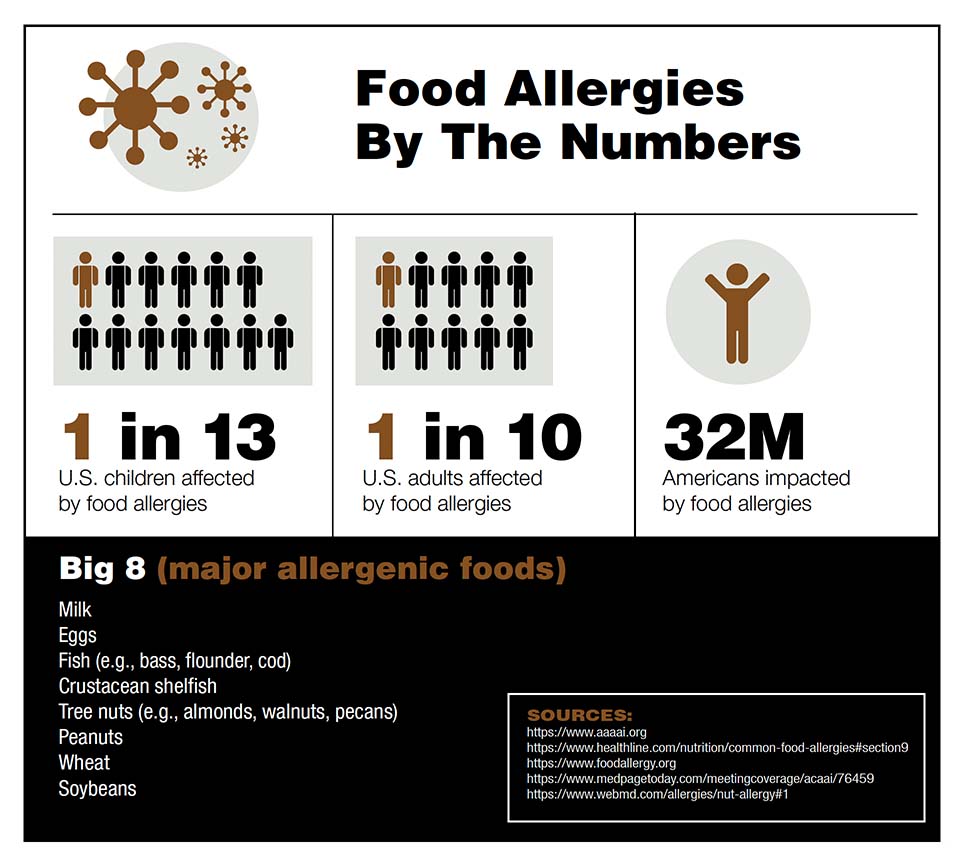

When it comes to food allergies, peanuts are considered one of the eight major foods that account for most food allergy reactions. In addition to this favorite legume, the big eight include milk, eggs, fish, crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, wheat, and soybean. According to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, peanuts are the leading cause of food allergies in children. FARE, a national nonprofit focused on food allergy research and education, notes that 32 million Americans, or one in ten adults and one in 13 children, have a food allergy. In a recent National Institutes of Health-funded study, scientists found that introduction of peanuts early in life significantly lowered the risk of developing peanut allergy by age five. However, for those who have an adverse reaction to nuts, MAFES researchers hope to find better ways to mitigate peanut allergies by turning to the legume itself.

Drs. Jiaxu Li, associate professor in the Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Entomology and Plant Pathology; and Sam Chang, professor in the Department of Food Science, Nutrition and Health Promotion working in the Coastal Research and Extension Center; along with former doctoral student, Dr. Shi Meng, embarked on three different studies to investigate the allergens in peanuts.

A peanut allergy might seem like a simple thing, but it's a little complicated. Peanuts have up to 17 allergens with four, in particular, considered the most potent.

Allergic reactions are caused when individuals develop specific Immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies to Arachis hypogaea (Ara) or peanuts.

"The problem is that there isn't only one allergen in peanuts. We studied the four most potent ones, which are Ara h 1, Ara h 2, Ara h 3, and Ara h 6. Ara h 2 is considered the most potent for severe allergic reactions and higher IgE-binding properties," Li explained. "Currently, the only available treatment is complete peanut avoidance, which is difficult given that peanuts are such a common ingredient in processed food."

In the first study, the team tested the allergenic potency of more than 100 peanut varieties to determine which varieties were the least potent. The second study focused on how cooking peanuts might change the makeup of those allergens. The last study analyzed how enzymatic processing, a chemical reaction that alters the peanut but preserves the legume's protein, might reduce or even eliminate those allergens.

First, the team partnered with Dr. Naveen Puppala with the New Mexico State University Agricultural Science Center. Puppala grew 122 varieties of peanuts at the research station in Clovis, New Mexico over the course of two years. After harvest, the MSU team screened each variety to measure the potency of each allergen present in the plant

"We tested the four major allergens in all 122 varieties and found significant decreases in allergens in nine of the varieties," said Li, who is an expert in studying the biochemistry of allergens.

In the second study, researchers found that while fried foods might not be the healthiest option for dinner every night, when it comes to peanuts, eating them fried might actually be a good thing, at least when it comes to the potency of the legume's allergens.

The researchers tested how boiling, high-pressure boiling, steaming, high-pressure steaming, frying, roasting, and microwaving peanuts reduced the allergens within, comparing the allergens found in the cooked legumes to those in raw peanuts.

The team used a kinetic model to characterize how allergen content changed during the cooking process. The researchers analyzed the major components that make up peanuts-moisture, lipid, protein, ash, and carbohydrate-under the various cooking methods. They also analyzed the IgE-binding properties of the four major peanut allergens.

"Thermal processing can alter the structure of allergens, which are considered proteins. This may be reflected by a decreased solubility and changes in the appearance of the protein bands," Li said. "We found frying for six minutes was the only process, which greatly reduced the IgE-binding properties among the cooking methods studied."

In the last study, researchers liquefied the peanuts through enzymatic processing to see if that changed the potency of the allergens present. They studied eight different enzymes and found they were able to eliminate the allergens in three of those enzymes.

"While enzymatic processing fundamentally changes the peanut's form, this type of processing preserves the protein found in the peanut so it can be used as an emulsifier to stabilize beverage systems, such as high protein drinks," Li explained.

While Li's niece is allergic to peanuts, Chang has a granddaughter who has been allergic to peanuts and eggs for most of her life. She still can't eat peanuts, but at the age of eight, she's recently been able to eat some egg products.

"The effect of allergens change from person to person with vastly different sensitivities. My granddaughter has always been allergic to peanuts and eggs and as she's gotten older, she's been able to introduce some egg products into her diet," Chang said. "Our hope is to find ways to breed peanut varieties with less allergens while also finding ways cooking and processing can further reduce or even eliminate those allergens."

Both Li and Chang are hopeful the work they've done will help other researchers studying peanut allergens down the road.

"In the first study, we found out different varieties of peanuts have different levels of allergen potency. That's new. We also found that cooking changes the level of allergens. Then, we found that by hydrolyzing peanuts through enzymatic processing, we can reduce or even eliminate allergens. That's amazing to see," Chang said.

He continued, "This work will lead to other studies, which will continue to develop ways to reduce allergens and develop varieties that have less allergens in the plant. It's exciting to see how science can work to accomplish this. In the future, we also want to partner with medical researchers so we can eventually study how these advancements might better help those suffering from peanut allergies, in particular."

This research was funded by USDA-ARS. Collaborators included researchers from the University of New Mexico State University Agricultural Science Center at Clovis, New Mexico and the United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Services, Southern Regional Research Center in New Orleans. The research produced two peer-reviewed articles, featured in Food Chemistry and Food Chemistry: X., two top food chemistry journals.

We tested the four major allergens in 122 peanut varieties and found significant decreases in allergens in nine of the varieties.

Dr. Jiaxu Li