The information presented on this page may be dated. It may refer to situations which have changed or people who are no longer affiliated with the university. It is archived as part of Mississippi State University's history.

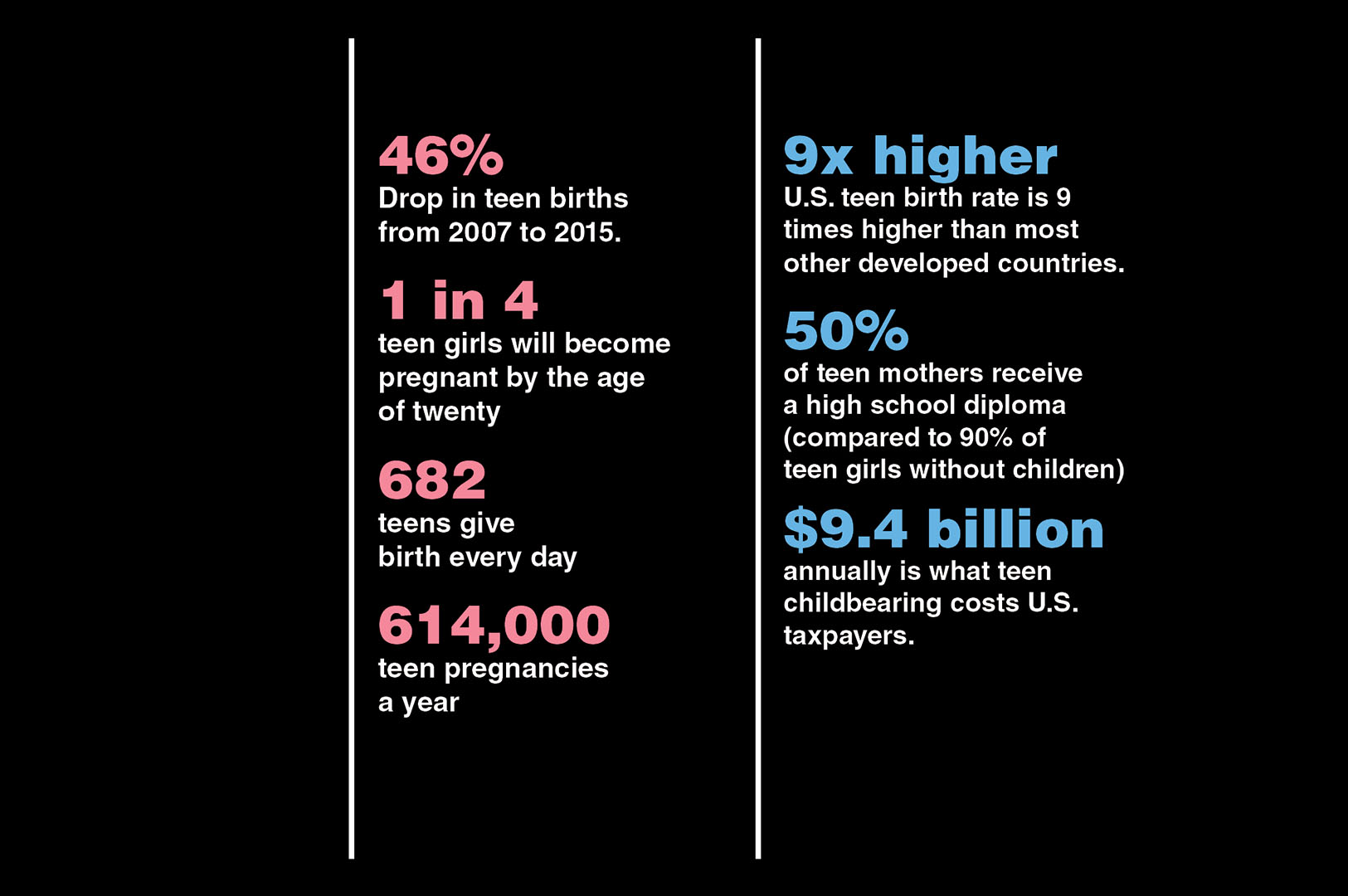

Even though teen pregnancy is down more than 25 percent nationally and in Mississippi, there is still much work to do to reduce the U.S. teen birth rate, which remains one of the highest among developed countries worldwide. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), one in four teen girls in the U.S. will become pregnant by the age of twenty. The numbers are greater in Mississippi, which consistently ranks among the highest in the nation in teen births. In the Mississippi Delta, those numbers are even higher. Access to safe and effective sexual and reproductive healthcare for at-risk teens is an essential component in reducing the number of teen pregnancies at the community, state, and national levels. Scientists in the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experience Station have partnered with Focus4Teens and its parent organization, Teen Health Mississippi, along with the CDC to provide community-level support they hope will ultimately improve outcomes for at-risk teens in the Mississippi Delta.

Teen Health Mississippi is the sexual and reproductive health and rights arm of Mississippi First, a non-profit organization specializing in education policy research and advocacy; Mississippi First received a $3 million grant funded by the CDC in 2015 to establish Focus4Teens, which is an initiative of Teen Health Mississippi. The initiative, now going into its third year, seeks to improve the quality of and access to sexual and reproductive health services for at-risk teens in the Mississippi Delta. The study encompasses three counties: Tunica, Coahoma, and Quitman. According to the latest available county data from 2014, in Tunica County, about 64 per 1,000 girls ages 15-19 become teen mothers; in Coahoma County that number is around 61 girls and in Quitman County that number is around 47 girls. The rates of births to teens in these counties are significantly higher than the teen birth rate at the state (37.9 per 1,000 females ages 15-19) and national (24.2 per 1,000 females ages 15-19) levels. Ancillary grantees are conducting similar studies in Durham, North Carolina and Savannah, Georgia.

Dr. Kathleen Ragsdale, MAFES scientist and associate research professor in the Social Science Research Center (SSRC), is the principal investigator helping Focus4Teens identify current barriers when it comes to teens gaining access to safe and effective sexual and reproductive healthcare. Dr. Mary Read-Wahidi, an SSRC assistant research professor, is the project's co-principal investigator. Their team spent the first two years of the study collecting baseline data through focus groups and in-depth interviews with those invested in the cause including parents, youth-serving organizations such as schools, and health clinics, and most importantly, teens themselves. One of the main goals was to determine barriers to seeking healthcare at community-based and school clinics as well as Title X clinics, which are federally designated to provide sexual reproductive health services.

"Our job is to make sure that teens who are engaging in risky behaviors are protected. We hope to provide resources for whatever risk levels people are at, in order to help them be healthy," Ragsdale said. "We work alongside our partner, Mississippi First, to collect data on how teens are using the facilities. We are also trying to help increase provider knowledge on how to reach out to youth and how to make sexual and reproductive health a natural part of healthcare."

In the first year, the team conducted focus groups with 35 teens ages 14-19. Ninety-seven percent were African American and 77 percent were female.

"The results of the focus group reinforce the need-from the teens' perspective-for a coordinated system for identifying, referring, linking, and providing evidence-based youth-friendly sexual and reproductive healthcare, including coordination between educators, parents and caregivers, social and behavioral support providers, and healthcare providers," Ragsdale said.

Ragsdale and Read-Wahidi found that confidentiality was an important barrier for teens.

"There is less anonymity in a small town," Ragsdale said. "That was one of the major barriers the teens cited as a deterrent to seeking this kind of care."

The team also conducted eight in-depth interviews with staff from four partner youth serving organizations as well as eight in-depth parent interviews. In addition, they interviewed 13 healthcare providers including doctors, nurse practitioners, licensed practical nurses, and clinic administrative staff. As a component to the interview process, they also conducted activities and administered surveys within the groups. They repeated interviews with other staff at the youth serving organizations and clinics in the second year.

Read-Wahidi discussed some of the other barriers teens face when deciding to seek sexual and reproductive health services at a clinic. One barrier was access to long-acting reversible contraception, such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) and subdermal implants. Ragsdale noted that the American Academy of Pediatricians has called these devices the best line of defense against teen pregnancies.

"We've found long-acting reversible contraception options were very limited in most clinics. In many cases, clinicians weren't trained to insert or remove them," Read-Wahidi said.

In some cases, access to shorter acting methods popular among teens, such as the Depo-Provera shot, was also hindered due to constraints such as health coverage.

"The other thing we discovered was that depending on the kind of health coverage you have, you may have to leave the clinic, drive to the pharmacy, pick up the Depo shot, bring it back to the clinic, and get the shot. Now, that's a big deal when you are a teenager that doesn't have transportation," Read-Wahidi pointed out. "Things like that can get lost in the data but make all the difference in a real-world setting."

In addition to transportation, cost and convenience were also cited as barriers. Read-Wahidi hopes identifying these barriers will help stakeholders find solutions.

"Ultimately, we want teens to feel welcome and comfortable in a youth-friendly environment. We want it to be easy for them to go to the clinic," Read-Wahidi said.

Ragsdale said the overall goal of the project is to help the community reduce teen pregnancy.

"We are trying to understand how teens, parents, youth serving organizations, and even churches work together as a community to help offset teen pregnancy," Ragsdale said. "We recently welcomed collaboration from two faith-based partners and we hope to get more churches involved. This kind of community involvement is essential."

Ragsdale also emphasized the importance of parental support in tackling the issue.

"It's best when the parents are engaged and involved in their child's healthcare," she said. "Many parents find it challenging to speak with their children about their sexual and reproductive health."

Ragsdale pointed out that Teen Health Mississippi tries to encourage parents to start having those conversations early and often.

"That way, by the time your child is a teenager you've already had plenty of those discussions. Even when they are little, when they start asking questions, it's important to discuss your values," she said. "We want to help parents give their children the tools they need to make good decisions as they become young adults."

Also serving on the project are Audrey Reid, a sociology master's student, and Katelyn Swiderski, a biological sciences senior. Other collaborators include Cicatelli Associates Inc. or CAI, a nonprofit capacity building organization that equips the workforce and community members to employ evidence-based strategies to promote equity in health outcomes for historically marginalized communities.

This publication was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number, #NU58DP006142, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.